| |

Why San Francisco Is (or Used to Be) Different:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

| San Francisco - numbers refer to places discussed in this article (click to enlarge) |

Most large cities are dominated by landowners and developers who form growth coalitions. But San Francisco has been different because it is a major city in which progressive activists and neighborhoods had a real and sustained impact for nearly five decades, and that's what makes it of theoretical relevance in discussions of urban power structures. The activists did not defeat the growth coalition, but they fought it to a standstill from the early 1970s into the early 21st century on issues that concerned the livability of neighborhoods and the preservation of urban amenities. They forced developers to create affordable housing and urban space they otherwise would not have provided in exchange for permission to construct new buildings. In addition, activists won "greater community-based participation in program design, land-use planning and 'constituency-sensitive' forms of service delivery" (Beitel, 2004,

At the same time, the downtown skyline was transformed by 30 million square feet of new office space between 1960 and 1980, and there were many further massive developments between 1994 and 2011 in formerly industrial, warehouse, and railroad areas, which shows that the growth coalition keeps on rolling along. It's also the case that the amount of affordable housing has been a drop in the bucket in terms of what is needed, which is in a sense a victory for the growth coalition. However, affordable housing and other small amenities extracted from developers by activists are nonetheless important in human terms, and they reveal the limits on the power of the growth coalition.

There were also the following successes for neighborhoods and progressive activists (numbers refer to the city map):

| 1959 | Upscale neighborhoods stopped a huge freeway through their area (#1) |

| 1965 | The anti-freeway forces joined with leaders in a predominantly black neighborhood to stop another leg of the federal highway (#2) |

| 1967 | A U. S. Steel building planned near the famous Fisherman's Wharf was blocked |

| 1968 | A Latino neighborhood was able to stop urban renewal planning (#4) |

| 1968 | A lawsuit filed in the federal courts by the San Francisco Neighborhood Legal Assistant Foundation on behalf of a black neighborhood group led to a preliminary restraining order to stop the federal government from supplying money to an urban renewal project until the Department of Housing and Urban Development lived up to its own regulations |

| 1970 | Another lawsuit filed by the San Francisco Legal Assistance Foundation led to a more sweeping injunction that questioned the substance of a relocation plan and halted an urban renewal project |

| 1975 | A newly elected liberal mayor included community-based organizations in the decision-making structure |

| 1978 | Strict rezoning laws provided comprehensive coverage to preserve existing residential densities and architectural styles in the face of new construction |

| 1986 | A strict growth control ballot initiative provided for a yearly ceiling on commercial office construction in a downtown that was losing sunshine and suffering from skyscraper-induced wind tunnels |

| 1990 | A ballot initiative that would have committed the city to help finance a new baseball stadium for the San Francisco Giants was defeated |

| 1998 | Comprehensive rent control and eviction restrictions provided true protections for tenants |

| 2000 | The progressives capitalized on newly instituted district elections to win a strong majority on the Board of Supervisors |

| 2004 | Growth-control activists defeated a deceptive pro-growth ballot measure put forth by the growth coalition by a resounding 69% to 31% margin |

Before discussing the details of these successes, and explaining how they show that the key battle in American cities is always between the landowners and developers at the heart of the growth coalition (whose primary concern is profits) and those who want to preserve neighborhood and environmental values ("use values"), it's important to note the growth coalition won several victories between 2005 and 2011, culminating in the election of a mainstream mayor and a "law-and-order" district attorney in November 2011. The city's population has grown older (including the activists who had so much impact), and Chinese-Americans -- who tend to be more conservative on both economic and social issues -- are nearly one-quarter of the population. The young high-tech workers in the city are very centrist and pragmatic on local issues. Reflecting the new trends, the city gave up tens of millions of dollars in payroll tax revenues to keep Twitter from leaving the city for cheaper rent elsewhere: a classic example of how businesses reduce city governments to beggars. On the other hand, some progressives still have important roles, so it's not as if liberalism is dead and gone. For further information on the situation as of 2011, two articles are useful: one from the New York Times, the other from San Francisco's perceptive on-line newspaper, BeyondChron: The Voice of the Rest.

Why were those victories possible?

What made that long string of successes from 1959 to 2004 possible, and do they contradict growth-coalition theory? They were made possible by a number of fairly unusual factors, and these factors accord well with the key feature of growth-coalition theory, which says that the basic axis of conflict facing a local government is between those who want to expand the downtown in order to make their land more valuable and those who want to protect the neighborhoods that are displaced or degraded by such expansion.

Not only are the findings on San Francisco congruent with growth-coalition theory, but they contradict other theories that have been suggested. For example, they do not fit well with political scientist Richard DeLeon's (1992) claim that the growth coalition fell apart in the face of an "anti-regime" of environmentalists, affordable housing activists, and neighborhood leaders that had the potential to turn into a "progressive regime" capable of governing the city. In fact, the growth coalition moved ahead with far more success than he predicted, with pro-growth mayors at the helm from the moment his book appeared to this day, 14 years later, which is not a bad run for an allegedly defeated growth coalition.

Nor does urban Marxist theory fare well in the face of the San Francisco experience. First, the unionized working class usually sided with the landowners and builders in the battles with neighborhoods, tenants, and activists, which makes it a stretch to call these conflicts "class struggles." Second, as pointed out by sociologist Karl Beitel (2004,

Before plunging into the details of the conflicts over growth and redevelopment, here are the three main factors that make San Francisco different:

- San Francisco is one of the most attractive and exciting cities in the country, which has two interrelated consequences:

- Companies are often so eager to locate their headquarters and hotels in San Francisco that they can be squeezed a little harder by public officials, if those public officials can be forced by activists and neighborhoods to make the squeeze.

- Many middle-class and wealthy people want to live in the city instead of moving to the surrounding suburbs, which means there is a solid basis for neighborhood and environmental protection movements.

- San Francisco has a history of open and contested politics due to the ballot initiatives made possible by Progressive-Era reforms in California and the city's once-strong labor movement, both of which date back to the turn of the 20th century (Walker, 1998).

- San Francisco is the home base for many 1960s civil rights and anti-war activists, who later turned their attention to the city as organizers for low-income housing, tenant rights, urban environmentalism, and neighborhood preservation. It was these activists, joined by neighborhood leaders, who made superb use of direct action, litigation, and ballot initiatives to overcome the problems of trying to bring about change within an electoral system where big campaign donors and pro-growth politicians have the initial advantage. The role of activists is just about lost in most current theorizing on social movements, which talks in terms of structures, opportunities, and resources, but activists are essential to social change, as long argued and demonstrated by sociologist Richard Flacks (1988).

Early planning, early battles: 1945-1970

|

| The San Francisco skyline today (click to enlarge) |

San Francisco was not always a city where activists mattered. From the end of World War II until the 1970s, the growth of San Francisco reads like a hypothetical example made up to illustrate Molotch's (1976; 1979) growth-coalition theory. The downtown growth elites, led by some of the largest corporations in the United States, and organized as the Bay Area Council, were out to "Manhattanize" the downtown, and they succeeded. The basic plan, which followed the same script found for other cities that have been studied in any detail, was to accelerate the dispersion of industry to outlying areas, roust out nearby low-income neighborhoods, and remake the city as a financial and office center. The plan also turned the city into a convention and tourist center: the number of hotel rooms rose from 3,300 in 1959 to 9,000 in 1970 to 30,000 in 1999 (Hartman, 2002,

Downtown land was simply too valuable for mere factories or neighborhoods. Besides, unionized workers gathered together in big plants were a problem anyhow, especially in a day when memories of the union upsurge of the 1930s were still vivid. As one San Francisco banker said in a debate at a local club in 1948:

Labor developments in the last decade may well be the chief contributing factor in speeding regional dispersion of industry.... Large aggregations of labor in one (central city) plant are more subject to outside disruptive influences, and have less happy relations with management, than in smaller (suburban) plants. (Mollenkopf, 1983,

p. 143 )

These plans were carried out by a semi-autonomous governmental agency called the Redevelopment Agency, which was created by the state legislature to carry out urban renewal with federal and state funds. Its somewhat independent stature was the result of suggestions from the national-level Urban Land Institute at the behest of growth elites who wanted to insulate urban renewal from citizen pressure and local politics to the greatest extent possible. The Redevelopment Agency's commissioners are appointed by the mayor and confirmed by the Board of Supervisors. (The Board of Supervisors is the San Francisco equivalent of a city council due to the fact that the city and county of San Francisco are coterminous.) The appointed commissioners then hire an urban renewal director and a large technical staff. The fact that the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency received major sums of money from the federal government -- $128 million between 1959 and 1971 -- meant that it often could do what it wanted to within fairly wide limits. As one expert on urban renewal delicately puts it:

Like its counterparts in other cities, the San Francisco Redevelopment Agency is a compound of public and private powers that provides a touch of the corporate state to local government in America. It can make and implement its own plans, move people from one section of town to another, arrange massive sums for financing, condemn property, and promote all its wonders. Traditional controls of public power, so endemic in American government, run a little thin with these agencies. (Wirt, 1974,

pp. 297-298 )

To maintain some local control over the Redevelopment Agency in addition to the mayor's appointive powers, the federal law that created the urban renewal program required that the mayor also appoint a local Citizens' Advisory Committee to oversee the agency. In San Francisco this role was played by an association of top business leaders called the San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association, which included most of the business leaders who had called for urban renewal in the first place (Hartman, 2002,

While the Redevelopment Agency was taking shape in the late 1950s, an area-wide corporate group, the Bay Area Council, of which the San Francisco Planning and Urban Renewal Association was in effect a subcommittee, was making plans for the construction of a rapid transit system that would carry employees and customers to the city from all over the Bay Area (Whitt, 1982, Chapter 2). Corporate-backed planning and construction also began on major freeways that would criss-cross the city, impacting many different neighborhoods, some of them decidedly upscale. It was here that the growth coalition began to generate some serious opposition.

A proposed leg of the freeway that would have cut through middle- and upper-middle class neighborhoods as it moved along the shore of the San Francisco Bay to the Golden Gate Bridge was halted in its tracks in 1959 by a coalition of merchants and neighborhoods (#1 on map). This victory provided activists with a permanent reminder of their success because the already built portions of that freeway, high on large cement pillars, were not dismantled. In fact, Beitel (2004,

The destruction of a black neighborhood

The original battles over urban renewal were fought in the Western Addition, not far from the downtown (#2 on map). The first part of this project started in 1962 and displaced approximately 4,000 people. There was relatively little protest because families who owned their homes were able to cash out and move to African American neighborhoods across the bay in Oakland and Richmond, while those who were renters relied on reassurances that there would be adequate relocation payments and help in finding housing of comparable cost. But by the time the second part of the project began in 1965, there was far greater resistance because it was now clear that those who were displaced would have to fend for themselves and most likely would be forced to pay higher rents in the growing black neighborhood at Hunter's Point, at the south end of the city (#3 on map). In addition, there were black and white civil rights activists who were ready to help defend the neighborhood. Moreover, they were initially supported by some union leaders, especially from those unions, like the longshoremen, that had a significant number of African American members.

However, in a microcosm of the nationwide divisions that mushroomed in the crucial years 1965 to 1967, the traditionally white unions in some labor sectors gradually sided with the growth coalition for a complicated set of reasons. Those reasons started with their desire to create more jobs for construction and hotel workers, but at the same time they involved the fact that white union members resented black activists who were demanding the integration of basically all-white unions as well as the assurance of jobs for African Americans on any redevelopment projects in their neighborhood. These deeply rooted schisms were widened by the growing union support for the Vietnam War at the same time that most African Americans were coming to oppose it in the name of greater attention to the many problems the country faced at home. (Recall that Martin Luther King, Jr.'s, opposition to the war made him persona non grata with the corporate moderates who had come to support the movement for civil rights.) From that point on, most unions -- led by the building trades unions and the restaurant, hotel, and bartenders' unions -- sided with the growth coalition on urban renewal in the name of "more jobs," while becoming more and more blatant in their unwillingness to desegregate their unions, thereby further embittering the African American community. The once powerful and militant longshoremen quietly stepped to the side.

While all this was going on, and the leadership of the local Democratic Party was appointing mainstream African Americans and trade union leaders to local government positions, another 10,000 people, mostly African American, were displaced from the Western Addition. Along the way, and crucially, the area's thriving retail and entertainment district was destroyed. Rather stunningly, most of the area then laid vacant for a quarter century, leading to further alienation and decline in the African American community:

The neighborhood once touted by residents as the "Harlem of the West Coast" was a shell of its former self. Gone were the jazz clubs, the night spots, small neighborhood retail shops, and church fronts that had once crowded along Fillmore street. Nor would any redevelopment in the razed commercial corridor along Fillmore Street be forthcoming, as the six square blocks in the center of the A-2 area would remain vacant for almost 25 years. San Francisco's black population, which had grown steadily between 1940 and 1970, would subsequently decline, and with it the political clout of the city's black leadership. (Beitel, 2004,

p. 47 )

To the degree that there was any redevelopment in the Western Addition after most of it had been razed, it was through highrise apartments, office buildings, and a Japanese Trade and Cultural Center in honor of the gradually disappearing Japanese-American neighborhood on the edge of the Western Addition. There was virtually no affordable housing included in the project. For those who wonder why African Americans used to call urban renewal "Negro removal," the story of the 14,000 people pushed out of the Western Addition drives the point home.

Although it was of little consolation to those who were displaced, the confrontation over urban renewal in the Western Addition did lead to the first legal victory for activists concerning the rights of those being displaced by an urban renewal project under the auspices of the Redevelopment Agency. In a suit filed by the San Francisco Neighborhood Legal Assistance Foundation, one of 300 such entities financed by the federal government's Office of Economic Opportunity as part of the War on Poverty, a federal judge ruled in late 1968 that the flow of federal monies to the project had to be stopped because there was no real plan to relocate the thousands of families that would be displaced (Carlin, 1973). His ruling was a procedural one, stating that the agency had not lived up to federal guidelines, and it was lifted two weeks later when the Redevelopment Agency promised that it would comply, but a precedent had been set.

Neighborhood victory in the Mission District

Although the Redevelopment Agency was able to buy up and knock down many blocks of the Western Addition, it was not able to do so in 1968 in another low-income area it had targeted, a Latino neighborhood to the south of the business district known as the Mission District (#4 on map), long the home to the new immigrants who do the janitorial and other service work for those in the central business district. Instead, the Redevelopment Agency drew back in the face of organized opposition from the Mission Coalition Organization, which claimed to represent over 200 community organizations. In the wake of their success, the community groups soon began applying for various kinds of federal funds related to the War on Poverty, and then created the Mission Housing Development Corporation to build or rehabilitate affordable housing, exactly the kind of nonprofit organization advocated for inner cities by the Ford Foundation. Organizations in the Mission District received $15 million in federal funds between 1971 and 1980 (Beitel, 2004,

Stand-off over Yerba Buena

The incursions into the Western Addition and the Mission District were paralleled by a long, bitter, and precedent-setting struggle in a neighborhood just south of Market Street, the major downtown thoroughfare as well as the key dividing line between the central business district to its north and the several miles of inviting flatlands to its south. The growth coalition wanted the Yerba Buena adjacent area just south of Market Street (#5 on map) for a convention center, cultural buildings, and more office space. This move was the logical next step for a downtown area that was hemmed in by the bay to its west and hills and established neighborhoods to its north. In the long run, the growth coalition envisioned moving even further south into the sprawling areas that contained small factories, warehouses, and railroad yards that had clearly seen better days and were headed for obsolescence. However, such plans were far in the future, and did not materialize until the 1990s, when San Francisco suddenly entered into a growth period that no one had foreseen.

In the 1960s, the immediate objective was to completely remove the Single Room Occupancy hotels, small apartment buildings, houses, and neighborhood retail stores that were used by the several thousand people who lived in the neighborhood. Yerba Buena was depicted as a skid row by the growth coalition and the widely read morning newspaper, the San Francisco Chronicle, which happened to own land at the edge of the area. In fact, it was a neighborhood of retired and disabled white workers, mostly male, living on their pensions, along with merchant seaman on layover and immigrant families of Asian and Filipino heritage. Some of the white workers had been members or organizers in left-leaning unions like the longshoremen.

|

| George Woolf |

|

| Peter Mendelsohn |

Little or no replacement housing was planned for residents of Yerba Buena. The Redevelopment Agency claimed there was no need for such planning because normal turnover in low-rent housing would take care of those displaced. It relentlessly bought up the Single Room Occupancy housing and put pressure on residents to leave, but some of the old leftists resisted, led by George Woolf, an 80-year old Communist who had tried to organize cannery workers in the 1930s. He was soon joined by Peter Mendelsohn, a 65-year-old merchant seaman who also had been a union organizer and a Communist. The resisters naturally turned to their former unions for help, and at first the mythic leftist leader of the longshoremen, Harry Bridges, seemed sympathetic. But the growth coalition won him over with the argument that factory and port jobs were going to leave the city anyhow. Moreover, the Building Construction Trades Council, which spoke for all the construction unions, took the lead on this issue by proclaiming that it made no sense to give up the potential construction jobs because Yerba Buena was not worth saving. In addition, the bartenders, hotel workers, and restaurant workers' unions also were in favor of expanding the downtown to create more jobs for their members.

The main demand of the Reds-

The stalemate created by the injunction dragged on for six months before the Redevelopment Agency signed an agreement stating that it would provide 4,000 units of replacement housing. However, it soon became apparent that its autocratic director had no real intention of fulfilling this agreement, which led to further legal action and pressure on the Redevelopment Agency from the mayor's office. Finally, after the death of the long-time director in late 1971, the Redevelopment Agency signed an agreement in May, 1973, to give TOOR's newly founded community development corporation the right to build 400 units of affordable housing in the area with federal money (Hartman, 2002,

|

| TODCO's Woolf House in (click to enlarge) |

By June, 1979, TODCO, performing the coordination functions carried out by any other contractor, had completed a nine-story apartment building with 112 units, which included street-level store fronts and rooftop gardens. A second building with 70 units came on line in 1982, and two more followed. Two of the buildings won design prizes. Moreover, the 1973 contract with TODCO to use federal monies to build subsidized housing transcended Yerba Buena in terms of its implications for San Francisco in general. It was around this time that Redevelopment Agency and city officials, facing both a cutback in federal funds as well as a continuing pro-neighborhood insurgency, gradually came to realize that it made sense to work with nonprofit, community-based organizations to provide affordable housing for low-income residents. By 1984, the several community development corporations in the city "were receiving more housing funds than the Redevelopment Agency, making them the single largest conduit for low-income housing production in the city" (Beitel, 2004,

Once the agreement with TODCO was signed, the Redevelopment Agency was able to move ahead with its plans for office buildings. But it wasn't until 1981 that a convention center was completed due to interminable arguments and lawsuits over financing and design. During the 1980s and 1990s various cultural centers and tourist attractions finally were added to the area. In a recent overview article in a planning magazine on how the area turned out, the author noted that the attractive affordable housing added greatly to the ambience of the area. That is, Yerba Buena had more life to it because it included low-income housing that the growth coalition and the Redevelopment Agency resisted tooth and nail. To make this point, the article quoted one of the radical planners, Chester Hartman, who had opposed the developers over Yerba Buena, and then wrote books in 1974, 1984, and 2002 that chart the changes in the city in colorful detail:

Yerba Buena certainly accomplished its purpose of creating a larger downtown, but what's interesting is that because of the tenacity of the opponents, you've also got a lot of nice low-income housing, plus more cultural institutions than would have happened otherwise. And the low-income housing isn't isolated, either geographically or culturally. (King, 2005,

p. 12 )

|

| Yerba Buena Gardens, which sit atop the (click to enlarge) |

Since everyone now agrees that the housing in Yerba Buena adds to the character of the area, the big question is why the Redevelopment Agency was unwilling or unable to meets its legal mandate and avoid all the trouble that followed. One plausible answer is that it would have been expensive, but bigger sums have been spent on many other development projects. I think there are two deeper, intertwined issues. One is the arrogance of power. The growth coalition leaders and the Redevelopment Agency officials thought the "bums" could simply be pushed out of the way, so why bother to be decent. Hartman's books (1974; 1984; 2002) record many arrogant and nasty comments to this effect by corporate leaders and government officials. The other issue is the bitter opposition the real estate interests always mount against any government "interference" in the housing market. They are so rigidly, ideologically anti-public housing, even though they have reduced public housing to a pittance, and isolated most of it into African American neighborhoods, that the thought of convincing them to allow a little more public housing was too much for any of the city officials, elected or appointed, to contemplate. They just didn't want the hassle.

Victories for the better-off neighborhoods: 1972-1978

As the downtown building boom and the arguments over Yerba Buena continued, ferment developed in better-off neighborhoods over the increasing construction of highrise apartments. This new thrust into neighborhoods by space entrepreneurs provided the opening that urban environmentalists, affordable housing advocates, and neighborhood preservationists needed to form a loose-knit coalition that could further their somewhat separate, but related agendas. The activists pursued these goals through several avenues, depending on their tastes and different interests, including demonstrations, litigation, ballot initiatives, appearances before city commissions, and involvement in electoral politics. One type of ballot initiative called for height and zoning restrictions that they felt were necessary to save neighborhoods. Another type called for changes in the election rules so that supervisors would be elected in district elections, not citywide elections. (For evidence that citywide elections in the United States were meant to defuse opposition to the growth coalitions, see the article on this site about power at the local level.)

It is important to note that many of the progressive activists had been part of earlier social movements and were looking for a new focus. Several of them had been students in the 1960s at San Francisco State University. As one of the long-time leaders in the coalition, Calvin Welch, explained to Beitel (2004,

The antiwar movement and the whole political explosion of McGovern in 1972 produced this set of political activists who didn't have a subject. They had certain skills, understood the role of big moral issues and electoral politics, but didn't have a local context for that to work out. They could understand the war, they could understand civil rights, they could understand McGovern but they couldn't understand Joe Alioto [the mayor in the late 1960s and early 1970s], they couldn't understand the Redevelopment Agency, they couldn't understand why so many people were opposing the freeway. So, a few of us kind of linked all those things up, and created a set of relationships, basically introduced people, putting together all kinds of people -- the growing environmental movement, the anti-freeway forces, the folks opposed to redevelopment."

Faced with growing neighborhood complaints, and hoping to strike a compromise between the growth coalition and the neighborhoods, in 1971 the City Planning Department proposed a 40 foot height limit in all neighborhoods, except for 11 "highrise zones" along the rapid transit lines that could have buildings up to 300 feet. This idea upset even more neighborhoods and led to a ballot measure (Proposition T) during the same year that called for an overall height limit of 72 feet. That measure lost 62% to 38%, and a somewhat weaker one lost 57% to 43% the following year, but it was now clear to city officials that the neighborhoods would have to be accommodated. Individual neighborhoods began to win "neighborhood-specific rezoning" while the more progressive, citywide activists prepared a comprehensive ballot measure that would protect all neighborhoods.

|

| George Moscone |

|

| Sue Bierman |

By early 1975 the activist groups had shown enough strength to be invited into an electoral coalition created by a liberal state legislator from San Francisco, George Moscone, who wanted to be mayor. His subsequent victory that fall marked another turning point in the ongoing battle because he appointed a long-time activist, Sue Bierman, dating back to the anti-freeway struggles, to the City Planning Commission. She convinced the commission to charge developers what came to be called a "linkage fee," meaning in effect a special tax for each project, which would be put in an earmarked fund for affordable housing or the city services needed to cope with mammoth office buildings and their large number of employees. (Developers, although they protested to begin with, did not find these fees too onerous, and soon came to considered them as a cost of doing business.)

The new mayor also directed that more city money be used to fund community-based organizations, especially when the money came to the city from a new federal program called Community Development Block Grants, which gave cities more discretion in how they used federal subsidies than earlier programs like urban renewal and Model Cities did. The combination of Moscone's liberalism, declining city revenues, and federal block grants meant that service-oriented nonprofits as well as housing-oriented community development corporations were being incorporated into the governance of the city, with a special focus on low-income populations. As Beitel (2004,

Fiscal austerity has forced urban governments to find cheaper ways to deliver services through the development of contracting relations with nonprofit agencies. Nonprofits generally pay lower wages than municipal agencies, and thus provide low-cost alternatives for delivering a (reduced) level of social services. To give just one example, in San Francisco the Department of Public Health formerly staffed and administered nine public health centers, whereas today [2003] all nine centers are administered by nonprofit agencies under contract with the Health Department at wages well below city scale."

This quasi-incorporation turned out to be a double-edged sword for the activists themselves. On the one hand, their low pay and lack of formal government position allows them to stay independent and maintain their advocacy stance for low-income and minority populations. However, the kind of service work for constituents they end up doing routinizes their activities and limits the time they have for organizing; they are also constrained in their activism by their constant need to ask for money from foundation and all levels of government (Shaw, 1999, Chapter 5).

At the time, however, the dilemmas of government involvement as service providers were still in the future, and the activists went on to chalk up another success in 1976. Their ballot initiative for district elections passed by a 52% to 48% margin, winning by strong margins in eight of the proposed districts after losing by overwhelming margins in the three wealthiest districts (which previously had provided most members of the Board of Supervisors). Unfortunately, this victory turned out to be a short-lived one because it was overturned by voters in 1980. (The city returned to district elections in 2000, but that gets ahead of the story.)

The loss of districts aside, the activists achieved their major goals as far as neighborhoods were concerned when the supervisors voted in 1978 to set a 40-foot limit on all buildings in residential areas, which could be altered only under special review. According to Beitel (2004,

Controlling the growth of office space: Victory in 1986

Despite these various successes, the activists had not been able to slow the growth of office buildings in the downtown area because the hands of the Planning Commission were tied in one way or another when it came to approving specific projects. The commission therefore ended up approving 8.2 million square feet of new office space between 1975 and 1979 even with its Moscone appointees and pressures from the activist groups, about the same as the 8.5 million square feet approved in the preceding five years. The activists therefore regrouped once again to create a ballot measure that featured growth caps on office space and linkage fees for affordable housing. Crucially, it also included provisions for neighborhood protection, historic preservation, abatement of traffic, and protection of small businesses serving neighborhoods, along with a powerful weapon for neighborhoods called "discretionary review," which allowed those near a project to call for a special review, making it possible to cause deal-killing delays or exact concessions (Beitel, 2004,

The activists lost on this measure in 1979 by 54% to 46% after being outspent by $500,000 to $30,000, and again in 1983 by a much narrower margin, 50.6% to 49.4%, even though they were outspent by $700,000 to $60,000. In 1986 they came back more united than ever to face a fragmented growth coalition that had lost some key companies to mergers with corporations in other cities and that was saddled with a glut of office space due to overbuilding in the first five years of the decade. The high vacancy rate meant that owners of established buildings were not as eager to fight controls on new office space as the developers were. In fact, the Chamber of Commerce, the usual leader of the pro-growth forces, chose to sit this one out, and business opposition was half-hearted. Only a last-minute campaign led by Mayor Diane Feinstein, herself the owner of two medium-sized luxury hotels near the most exclusive shopping area, and now a Senator from California, kept the margin of victory from being a large one. San Francisco now had what DeLeon (1992.

Surprisingly, the downtown growth leaders claimed not to mind too much when they were interviewed a few years later as part of a study comparing growth strategies in San Francisco and Washington (McGovern, 1998). Maybe they were simply trying to look good in print, but some of them said that it made sense to build at a more stable pace, and that it was right that developers should have to help with affordable housing. Or maybe they knew they could find loopholes when vacancy rates dropped again, as proved to be the case in the 1990s. They also knew that they had plenty of approved projects sitting in the "pipeline." In any event, requests for approval never exceeded the limits set by the 1986 initiative because market demand was never as strong as it once had been.

From the point of view of the neighborhood activists, the 1986 initiative victory solidified the gains they had made in the previous ten years through its provisions for neighborhood protection, abatement of traffic, and support for small businesses serving neighborhoods. The established middle-class neighborhoods could breathe a sigh of relief. For the citywide progressive activists, however, this success meant that the neighborhoods north of Market Street, where most of the middle class, upper-middle class, and very rich live, would not be as easily mobilized to help in future conflicts that might arise for low-income neighborhoods that were south of Market Street, such as the Mission District. It also meant that middle-income neighborhoods, whether north or south of Market Street, could use some of the provisions in the 1986 ballot initiative, and especially discretionary review, to block progressive attempts to put affordable housing in their neighborhoods. They also could oppose nearby commercial developments that were sought by low-income neighborhoods. In other words, the neighborhoods could retreat into NIMBYism.

As the next section shows, this is in good part what happened with the big developments south of Market Street that were proposed in the 1990s. Because they involved predominantly non-residential warehouse and railroad areas that were no longer used, and often abutted lower-income neighborhoods, the middle-class neighborhoods were less interested in challenging them, leaving the affordable housing activists and environmentalists to fend for themselves. This changing constellation of forces meant that some new and unusual alliances would emerge. On the one hand, the growth elites had learned that they needed to include affordable housing and other linkages (e.g., parks, open space, money for public transportation) if they were going to succeed. On the other, the housing activists were looking for places to put affordable housing because the established neighborhoods were not interested in having any.

The roaring 1990s: Contra DeLeon

San Francisco in the 1990s takes on special theoretical interest in terms of assessing the adequacy of rival urban theories because DeLeon concluded that it had become a "wild city" during the 1980s, with no one group in a dominant position and everyone able to block everyone else. As of 1991, according to DeLeon (1992,

(Catellus started as the real estate development arm of the railroad company that once dominated California politics, the Southern Pacific, which merged with the Santa Fe railroad in 1983 to create Santa Fe Pacific, which sold the former Southern Pacific's rail lines to Rio Grande Industries in 1988 and split into three independent units in 1990, one of which was Catellus. To bring this complicated genealogical story up to date, what remained of Santa Fe Pacific was merged into another railroad giant, Burlington Northern, in 1995 to create BNSF, and in July, 2005, Catellus was sold to a worldwide development corporation based in Denver for an estimated $4.9 billion.)

DeLeon did hedge his bets slightly by adding a postscript just before the book went to press due to the fact that a pro-growth, law-and-order Democrat, Frank Jordan, had been elected mayor in 1991, replacing the more liberal Art Agnos. DeLeon then proceeded to list the several blind spots and weaknesses the progressive forces would have to overcome to solidify into a regime capable of governing. Even with the caveats, however, DeLeon turned out to be mostly wrong about just about everything, showing again that no one can predict the future, least of all when they bet against the growth coalition. The city soon entered into an unprecedented downtown expansion without discomfiting any established neighborhoods, which largely stayed out of the fray. The primary opposition to these developments came from environmentalists, affordable housing activists, and low-income neighborhoods. However, tenant-rights activists, who had been slowly building their forces throughout the 1980s, did win some significant battles to protect low-income renters during this decade (Shaw, 1998).

Here are the highlights of the story that will now be told:

- A new baseball stadium was constructed for the San Francisco Giants in the China Basin area south of Market Street, leading to an explosive rise in nearby land values (#7 on map).

- An unexpected opportunity arose for developing the beautiful army base known as the Presidio, which contained 5% of the city's land mass (#8 on map).

- A dramatic expansion of the downtown was made possible through the development of the railroad yards at Mission Bay owned by Catellus, which carried out its plans with the help of its lawyer-lobbyist, who became mayor in 1995 (#6 on map).

- The conversion of massive amounts of old warehouse space into offices was accelerated by the dot.com boom that swept through the city between 1995 and 2000 (#9 on map).

- A new headquarters in the Mission Bay development for biotech research was made possible in 2004 by a $3 billion dollar initiative passed by California voters for stem cell research.

- There was a rise in residential rents of 300% between 1993 and 2000, which greatly benefited landlords in a city where two-thirds of the residents are renters.

Small wonder, then, that San Francisco was the top real estate market in the United States from 1996-2000 (Hartman, 2002,

The ballpark is built after all

|

| AT&T Park, née (click to enlarge) |

When DeLeon left off the story, voters had rejected paying for a new downtown baseball stadium for the San Francisco Giants. In 1993 the disappointed owner sold the team, which he had purchased for $8-10 million in the 1970s, for $100-115 million to a consortium of local owners, led by a multimillionaire grocery chain heir, but including the top downtown real estate owner. Realizing the public could not be persuaded to pay for the park, the new owners readily worked out a financing package that included only a small amount of government funding. The deal was approved by voters in 1996 by a solid margin and the new park opened to year-long sellout crowds in 2000. The value of property in the nearby area skyrocketed, as expected.

The Presidio

About the same time that the ballpark was becoming a possibility again, an unexpected opportunity for further development opened up because the Department of Defense announced it would close its historic army base, the Presidio, situated on 1,480 acres of prime land where the San Francisco Bay flows into the Pacific Ocean, near the entrance to the Golden Gate Bridge. This forested setting, resplendent with beautiful officers' quarters -- many of them mansions -- as well as barracks, a hospital, and a golf course, was as perfect a site for development as could be imagined.

|

| Fort Scott, part of the (click to enlarge) |

From a developer's point of view, however, there was one problem. Liberal Democrats in Congress in the 1970s, looking far into the future, had made the area a part of the Golden Gate National Recreation Area controlled by the National Park Service. Since there obviously was no longer any need for a fort to guard the entrance to the San Francisco Bay, they knew the army would eventually abandon it. Thanks to Republican control of Congress starting in 1994, however, the problem created by the liberals was solved by creating a Presidio Trust within the park service that had to earn its own keep by 2013, to the tune of about $36 million a year, or be sold by the General Services Administration as excess property. This of course meant that there would have to be some major money-making developments. The San Francisco growth coalition then gained control of the action by having the Presidio Trust turn over management of its affairs to the Golden Gate National Park Association, a private organization led and financed by centimillionaire and conservative Republican Donald Fisher, founder of The Gap, who had the help of executives and donations from other major companies in the city. Through the use of long-term leases, there has been a de facto privatization of the area (Adams, 2004; Beitel, 2004,

|

| Lucasfilm's Digital Arts Center (click to enlarge) |

The first major tenant, Lucasfilm, most famous for the Star Wars movies, provides San Francisco with yet another tourist attraction, as well as a magnet that could turn the city into a "digital Hollywood." In addition to movies, the company, which had estimated revenues of about $1.2 billion in 2003, also makes video games through LucasArts, and is a leading designer of movie special effects through Industrial Light and Magic. Its new $350 million headquarters houses 1,500 employees. Visitors can't enter the building, but they can press their noses against the glass walls and peek inside. They also can look at the new Yoda fountain near the entrance.

And sure enough, other entertainment attractions are joining the parade. In 2004 the heirs of Walt Disney chose the Presidio as the site for a museum to honor the life of their benefactor. They plan to put the memorabilia they have collected in a restored 100-year-old Army barracks. Still other parts of the old fort will be preserved as a tourist attraction in their own right.

The huge Mission Bay development

|

| Aerial view of the Mission Bay area (click to enlarge) |

The Mission Bay development on abandoned railroad yards in the South of Market area, just a mile or so from the main business district, is the largest development in the history of San Francisco. It's a $4 billion plan spread over 303 acres that "calls for an eventual 6,000 housing units, 1,700 of them subsidized to affordable levels; 860,000 square feet of retail space; a 500-room hotel; a public school; police and fire stations; four child care facilities; up to 51 acres of open space; and a public library" (Adams, 2002,

The Mission Bay project was over 15 years in the making and it looked very different at the start than it does now. Catellus, which you will recall started as the real estate development unit of the once-mighty Southern Pacific, first came to the city with a plan in 1981, but that plan was rejected immediately by city planners and Mayor Feinstein as unsuited for the city. The same thing happened again in 1983 even though the plan won design awards from planning groups and their magazines. There was so much office space in the second plan that planners saw it as competition for the already established downtown. At this point the city took the lead in suggesting a plan, which it produced in 1987. By that time the affordable housing and environmental activists had set up a united front known as the Mission Bay Consortium to discuss their own demands for the area, and they began to met with the developers and city planners through an informal network called the Mission Bay Clearinghouse. After many years of downtown conflict, all sides were ready to listen to each other in the hopes of a more harmonious process.

After another round of planning, a revised and expanded plan was approved by the San Francisco Board of Supervisors in 1991, but not before the developers lost a ballot initiative in 1990 in which they were opposed by both slow-growth activists and major downtown real estate owners in their attempt to be exempted from the constraints of the 1986 growth-gap initiative (Beitel, 2004,

Still, the plan approved in 1991 went nowhere because economic conditions were not right. Moreover, the development lacked a magnet tenant, the kind of major draw that could bring smaller enterprises to the area. So in 1993 Catellus announced that "it would create a 50-acre entertainment complex with a ballpark, arena, and cinema at the northeast corner of Mission Bay" (Adams, 2002,

Following that defeat, and facing some financial difficulties, Catellus gave up on a completely private plan and turned unexpectedly to the Redevelopment Agency so it would be able to receive some public funds. Among other things, this new arrangement made possible a favorable tax deal called "Tax Increment Financing," which means that the taxes collected from buildings on the land would be used to finance the rest of the project instead of putting the money in the general tax fund. Such financing is a bonanza for project developers, although not for the city, which has to find other sources to fund ongoing physical maintenance and social spending in the rest of the city.

|

| Willie Brown |

At that point Catellus also had the enormous good fortune to see one of its lawyer-lobbyists, the longtime Speaker of the California State Assembly, Willie Brown -- who had been pushed out of legislative office by term limits -- win election for mayor in November 1995. Brown, an African American from a low-income family in Texas, had been elected to the Assembly from a San Francisco district as far back as the 1970s, rising to the speakership against a rival Democrat by winning votes from a few Republicans in exchange for committee chairmanships for them.

An astute politician with charisma and good relations with just about everyone, Brown was a liberal on social issues and a supporter of labor unions, but he was also a lawyer in his spare time for major corporations, including development corporations. As early as 1982 he had been hired by Catellus to help it with land issues in San Francisco, initiating a land swap between the state and the city along the waterfront south of Market Street that was of benefit to the company. Brown would not disclose his fees, but the loose reporting categories on the conflict-of-interest forms he had to file with the state each year showed that during 1983 he received "over $10,000" from 13 corporations, including Catellus (Hartman, 2002,

Make no mistake, though. The election of Brown to mayor in 1995, and again in 1999, solidified the bonds between the growth coalition and city government in a way that turned the eight years he served into a heyday for landlords and developers. His network of funders, his support by organized labor, and his solid electoral base, along with the unexpected opportunity to appoint five members to the Board of Supervisors in his first two years in office, made him one of the most powerful mayors in the history of the city.

Right at this time Catellus notified the city that it was withdrawing from its 1991 development agreement with the Board of Supervisors to pursue a new project to build a second campus for the University of California's medical school. Although there had been preliminary negotiations with the university before the elections, things moved much faster with Brown, a former ex-officio trustee of the university by reason of his speakership position, due to be installed in city hall. By November 15, not long after his election, Brown announced that the university had accepted the offer of 43 free acres and would begin its planning process soon.

Shortly thereafter a blue-ribbon support committee called the Bay Area Life Sciences Alliance was announced. Chaired by Fisher, the aforementioned founder of The Gap who guided the Presidio takeover, the Alliance was a cross-section of leaders in the 1990s incarnation of the growth coalition, including several corporate lawyers from the most prominent firms in the city. The Alliance hired a former director of the Redevelopment Agency to be its own director, and entered into a contract with Catellus to be its project manager for construction, an arrangement that had the advantage of limiting public disclosures because the Alliance was a "public-private partnership" (Beitel, 2004,

The Alliance then began bargaining with the housing activists' Mission Bay Consortium, which realized that the Tax Increment Financing arrangement with the Redevelopment Agency meant that the project would have plenty of money for affordable housing. As Beitel (2004,

[The activists] saw tax increment financing sources as a potential boon to the construction of affordable housing. In addition, affordable housing advocates were encountering pervasive NIMBY sentiments amongst property owners associations fighting infill projects [i.e., projects on vacant or under-used land in a neighborhood] through lawsuits and lengthy court battles; Mission Bay offered ample siting opportunities and the ability to avoid protracted court battles."

As might be expected at this juncture, the developers and the activists were able to reach a fairly quick agreement. There was not quite as much affordable housing as there had been in the city-inspired plan of the late 1980s, but under the circumstances Welch considered it "a hell of a deal." The Mission Housing Development Corporation, still going strong in the Mission District, got the contract to oversee the construction of the affordable housing. The San Francisco Chronicle called it a "love-fest between former enemies" (Beitel, 2004,

Theoretically speaking, I would call this story a testimony to the flexibility of the growth coalition in the face of determined opposition, a vindication of growth-coalition theory, and a problem for DeLeon's (1992) claim that San Francisco had become a wild city in which the growth coalition had gone to pieces. It was difficult economic conditions and opposition within the growth coalition itself that caused most of the problems for Catellus in this development saga, not the wildness of the city. Despite the liberal political environment in the city, and the power of the activists, the amount of construction does not seem to decline when the economic conditions are ripe.

The dot.com boom -- and bust: 1995-2000

As the ballpark, Presidio, and Mission Bay deals were moving through the pipeline, yet another growth opportunity appeared due to the influx of young professionals into the city, a process in part due to the success of the activists in making San Francisco an environmentally attractive and livable city, but that was greatly accelerated in 1995 by the beginning of the dot.com boom. This nationwide mania generated an estimated 500-700 startup companies, many of them in San Francisco, that needed immediate space for work, leisure, and residency for the thousand of new employees. The needed space in San Francisco was provided south of Market through several ingenious, or perhaps diabolical, circumlocutions that bypassed most of the growth controls that had been put in place in the previous decade.

Slight changes in zoning regulations passed in 1988 provided the loophole for creating the needed residential space through the conversion of old warehouses into "live/work" space for artists. The zoning change led to a modest number of conversions and an influx of lower-income crowds like new artists and startup music groups in the first few years. However, developers were soon making these live/work lofts into attractive market-rate housing because they could convince their friends in the mortgage business to treat the lofts as housing for mortgage purposes. By then, of course, few of the buyers were artists. Most worked in finance, insurance, real estate, law, and after the dot.com boom got rolling, design , programming, and information technology. In addition, live/work space had lower school taxes than ordinary housing, and developers did not have to pay various fees because the space was not housing in the eyes of the city. In all, the city lost an amazing $81.3 million in fees in just a few years due to these tax loopholes (Beitel, 2004,

As for the office space needed for dot.com companies, it was created by saying the new office space, whether generated through conversions or new buildings, was really for "business services" or "research and development," which were not covered by the 1986 growth cap (Beitel, 2004; Hartman, 2002). The progressives quickly began to protest these subterfuges, and threatened to file suit, but in 1998 all 845 requests for permits to convert or build in the South of Market area were ultimately approved. When hearings were held in 1999 on a possible freeze in the granting of permits, developers sent 300 angry -- and burly -- construction workers to line the hallways leading to the hearing room, a clear attempt at intimidation (Beitel, 2004,

Because the new "live/work," "research and development," and "business services" spaces were in warehouse and factory areas, there was relatively little displacement of low-income residents. It was only the city treasury that was getting screwed. However, more traditional growth coalition tensions with neighborhoods began to develop by the late 1990s when the dot.com surge spilled into the Mission District, the longstanding Latino neighborhood of the city that had fought off urban renewal in the late 1960s (#4 on map). Although this influx caused little housing displacement, it threatened to drive up rents for the buildings used by neighborhood groups and ethnic small businesses. Evictions soon followed to make way for the dot.coms.

|

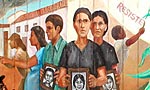

| Mural in the (click to enlarge) |

In 1999 a wide range of longtime progressive activists banded together to reign in the growth coalition once again, joining with the Mission District activists who worked in community development corporations and other nonprofit community organizations. The result was a ballot initiative for 2000 that would close all the loopholes that had accumulated since the 1986 initiative passed. Mayor Brown and the Democrats then countered with their own, weaker proposition. Despite spending $2.3 million and gaining the endorsement of the labor unions, Brown's initiative lost by a large margin, 61% to 39%. However, the activists' proposal also lost, although barely, 50.4% to 49.6%, which meant that everything remained as before as far as permit approval was concerned. "Live/work," "research and development," and "business services" were still operative euphemisms, and decisions about construction permits were back in the laps of the City Planning Commission.

Then, just as the two sides were gearing up for another round, the dot.com bubble burst. Vacancy rates rose very quickly in the entire South of Market area, including the Mission District. Several of the dot.coms that had taken space from poorly financed nonprofits went bankrupt. Although the pressure came off the Mission District, the various community-based nonprofits have remained vigilant. They now provide an organizational basis for a neighborhood leadership cadre that can draw on funding from various federal and state programs as well as from local liberal foundations (Beitel, 2004,

However, the highhanded actions of the developers and Brown during the dot.com boom had some unexpected consequences that added up to potential problems for the growth coalition. First, activists had been able to appeal to neighborhood self-interest in 1997 to win a return to the district form of elections that first had been won in 1976 and overturned in 1980. Second, the battle over the two rival ballot initiatives, in which Brown made a number of blatant power moves that angered many voters, led to the election of eight pro-neighborhood members to the Board of Supervisors in 2000. In most cases they defeated candidates picked or supported by Brown, so the election was a clear repudiation of his leadership. An 8-3 majority on the Board of Supervisors meant that the pro-neighborhood forces could override Brown's vetoes.

Success at last on rent control

Neighborhood protection and affordable housing advocates had greater visibility in the 1980s, but their counterparts in the tenant rights movement -- seeking rent control, protection from arbitrary evictions, and limits on the conversion of rental units to owner-occupied condos -- were also lobbying the Board of Supervisors and mounting ballot initiatives, although with less success. In the 1990s, however, with a renewed emphasis on economic fairness, along with a change of strategy to greater grassroots mobilization, the movement was able to win ballot initiatives in 1992 and 1994 despite massive expenditures by landlords. When a tight rental market in the mid-1990s tempted landlords into arbitrary evictions of longstanding tenants, the end result was another round of victories for tenant activists, this time with the support of labor unions, at both the Board of Supervisors and on a 1998 ballot initiative (Shaw, 1998). "By the end of 1998," Beitel (2004,

Neighborhoods divided

Although San Francisco activists have been able to protect neighborhoods, build some affordable housing, and institute rent controls, they have not been able to unite the neighborhoods into a progressive force. NIMBYism still reigns supreme. For example, when plans were unveiled in 1990 to put some low-income housing in the middle-class Potrero Hill neighborhood, the residents used every conceivable argument to stop the project, including the claim that the land was home to an endangered species of spiders (Beitel, 2004,

The illberal, even racist or reactionary, stances that are taken on some issues by some neighborhoods reveal the limitations of any analysis or hopes for the future based on the idea that there is a "progressive coalition" in San Francisco. It seems more accurate to say that there are temporary alliances between progressive activists and neighborhoods on some issues.

San Francisco today

Capitalizing on the respectability that the phrase "affordable housing" has gained, the Chamber of Commerce led the growth coalition into action on a "Workforce Housing Initiative" in early 2004 that actually was meant to increase the amount of market-rate housing near the downtown area, but was sold as a way to increase affordable housing. However, the slow-growth and affordable housing activists were able to convince voters that the measure had little or nothing to do with affordable housing, and it was defeated in a landslide. That defeat, combined with the presence of a pro-neighborhood majority on the Board of Supervisors, might give the impression that the growth coalition has now met its match. But the growth coalition does not give up easily.

|

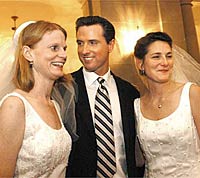

| Mayor Gavin Newsom, elected 2004 |

For one thing, the city had a personable new young mayor, Gavin Newsom, who was part of the growth coalition as a millionaire downtown businessman. He is also a classic growth-coalition politician in that his liberal social values are in keeping with those of the city, to the point where he attained national prominence by performing gay marriages at City Hall in the spring of 2004, helping to trigger a nationwide fervor over the issue.

For another, the growth coalition suddenly had a new opportunity in the fall of 2004 when California voters passed a stem cell research initiative that provides $3 billion over the next 10 years. These newly available riches started a bidding war among major California cities over where the research headquarters would be located. That war was won by San Francisco with the help of $17 million dollars in private funds raised by Newsom from Fisher of The Gap and other local centimillionaires, along with the offer of free acreage in the Mission Bay project (Marshall, 2005). It is now possible that San Francisco will become a major center for stem cell research as well as a "digital Hollywood."

|

| Proposed 61-story residential tower at |

The successful bid for the stem cell headquarters in turn led to the need for more upscale housing near Mission Bay, starting with 500-foot residential towers where small condos will be priced in the $1 million and up range. To meet this need, the supervisors suddenly and unexpectedly agreed to allow such towers in an area on the bay called Rincon Hill (#12 on map). The growth coalition and the supervisors were able to pull off this quick deal with relatively little protest because (1) they worked out the plan in secret and (2) the area is isolated enough that it does not directly impact any middle-class neighborhoods. In the end, though, the lower-income neighborhoods near Rincon Hill were able to pull themselves together and extract some fees for local community development.

How was this fast-track housing arrangement possible? Randy Shaw, a longtime tenant lawyer, activist, author, and close observer of the city, provided the explanation in an article he wrote on May 16, 2005. He began by stating the paradox of the growth coalition's successful new venture so soon after it lost on the affordable-housing initiative:

In March 2004, San Francisco voters rejected by a 70-30 margin a ballot initiative (Prop J) backed by Mayor Newsom and the Chamber of Commerce that sought to bring highrise condominium development to the downtown and adjacent areas. One year later, the chief objectives of Prop J have been met despite the electorate's rejection of this agenda at the ballot box. (Shaw, 2005a)

|

| Activist Randy Shaw |

He then goes on to explain the relationship between the growth coalition and the neighborhoods that made the Rincon Hill deal possible:

This is the historic trade-off for San Francisco. Over the past three decades the elite have been granted near exclusive power to redevelop vast stretches of the city, including the South of Market Area, the Western Addition, Golden Gateway, and the Presidio. Now they are moving in rapid fashion to create a new employment base for upscale residents in Mission Bay, with luxury housing for newly arrived residents at Rincon Hill... (Shaw, 2005a).

(Click here for the full text of the Shaw article, which is a great piece of power structure analysis.)

The post-2004 growth coalition has two other new projects on its agenda, although neither is as important as the new stem-cell headquarters and the condo towers. Both concern the remaining neighborhoods near the downtown and tourist areas. First, turn old apartment buildings, often occupied by low-income residents, into renovated hotels and motels for tourists, which of course means higher rents per square foot. Second, attract upscale residents to replace low-income residents by talking about loft living, gentrification, and the conversion of some of the old hotels into expensive apartments and condos of varying sizes and designs.

There are at least three reasons for this second objective. First, the city does need some residents if the central business district is not going to be a ghost town after 5 p.m. or when the tourists are not visiting. Second, upscale housing is now very profitable to build. Third, low-income residents can be expensive, especially when they can't find employment or their pensions aren't very good.

Although the conflicts generated by these twin downtown efforts are not on a plane with the high-profile contests of the past over tall office buildings, the issue is still landlords trying to increase the value of their land -- raise rents -- at the expense of residents, as growth-coalition theory would expect.

Conclusion

The 50-plus years of battle carried out by a determined band of progressive activists and neighborhoods in San Francisco led to many major successes that have put real limits on the worst excesses of the local growth coalition. These victories show what is possible under the right conditions with patience, sound strategies based on experience, and committed leadership, and they have made San Francisco a more livable city. The activists forced the city to deal with them, and they have become the voice for low-income communities through community development corporations and other community-based organizations.

However, they have not been not been able to curtail the growth coalition in its relentless search for profits through constant expansion and land-use intensification, nor to cause any significant redistribution in the immense wealth that has been generated due to the strategic location of the city and the collective abilities and work efforts of the 800,000 people who live there. The growth coalition did not fall to pieces (DeLeon, 1992,

Nor have activists been able to forge a progressive coalition capable of governing the city. This is not simply because of the limited number of progressives and some divisions among them on specific issues, or even their lack of financial resources, which are real enough problems, but because their neighborhood coalition partners are not an inherently progressive constituency. The first and foremost goal of neighborhoods is the protection and enhancement of their use values, which sometimes brings widely varying neighborhoods into coalition on important issues, such as limiting the incursion of highrises, and at the same time makes the progressive activists important allies.

However, there are also issues that divide the neighborhoods because of their very important class, ethnic, and racial differences, and on those issues the progressives are often seen as irrelevant or on the wrong side. This is especially the case where issues of racial integration or the placement of low-income housing are at stake, and most middle-class neighborhoods have little or no sympathy for the homeless or unemployed either. The major weakness of analyses of San Francisco by liberal and progressive scholars is that they are too hopeful about progressive politics because they do not take the more somber analysis of neighborhood politics by growth-coalition theorists seriously enough (Logan & Molotch, 1987, Chapter 4). As DeLeon himself later told the author of an article in the journal Planning, it is the neighborhood issues that matter:

Times have changed, suggests Richard DeLeon, a political science professor at San Francisco State University and author of Left Coast City, a political history of post-1960s San Francisco. "There's a preoccupation now with other issues." Rather than height and downtown growth, he says, residents are concerned with preserving the existing housing and employment conditions in their neighborhoods. (King, 2005,

p. 16 )

In other words, until progressives can find ways to forge programs that overcome the anti-tax and anti-government orientations seen as sensible and self-interested by most San Franciscans, they are fated to be the leaders in limited, single-issue struggles that can appeal to enough neighborhoods to win the day. Or as Shaw frankly stated in a critique of the self-limiting patterns into which the progressive forces have fallen:

For nearly two decades, the framework of San Francisco's budget has been largely unchanged. Almost every year a progressive coalition of labor and human services groups fights to maintain certain programs slated for cuts or elimination, and usually succeeds.

During this two-decade long City Hall budget battle, progressives have not waged a single well-funded and organized initiative campaign to force major downtown businesses to contribute additional resources to the city. Activists publicly demand that downtown "pay its fare share," but have not mounted a single well-funded, grassroots campaign to make this chant a reality.

After Supervisors voted for the business tax settlement in 2001, a resolution that has cost the general fund $30 million annually, vows were made that the beneficiaries of the deal would end up paying even higher taxes once voters could impose them on the November 2002 ballot (Shaw, 2005b).

But that ballot initiative never happened.

In closing, it would be foolhardy for me to project any trends. If you want to follow the ongoing battles between the growth coalition and its opponents in San Francisco, bookmark the activist web newspaper BeyondChron: The Voice of the Rest, at www.beyondchron.org. It appears five days a week and archives its past articles.

References

Adams, G. (2002). At Mission Bay, it's try, try again: Five attempts show how the best-laid plans can go awry. Planning, 68, 18-24.

Adams, G. (2004). Presidio Trust Management Plan, San Francisco. Planning, 70, 12-13.

Beitel, K. E. (2004). Transforming San Francisco: Community, Capital, and the Local State in the Era of Globalization, 1956-2001. Ph.D., Sociology, University of California, Davis, CA.

Carlin, J. (1973). Storefront lawyers in the ghetto. In M. Pilisuk & P. Pilisuk (Eds.), How we lost the war on poverty (

DeLeon, R. L. (1992). Left coast city: Politics in San Francisco, 1975-91. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

Fainstein, N., & Fainstein, S. (1983). Regime strategies, communal resistance, and economic forces. In S. Fainstein & N. Fainstein (Eds.), Restructing the city: The political economy of urban redevelopment (

Flacks, R. (1988). Making history: The radical tradition in American life. New York: Columbia University Press.

Hartman, C. (1974). Yerba Buena: Land grab and community resistance in San Francisco. San Francisco: Glide Publications.

Hartman, C. (1984). The transformation of San Francisco. San Francisco: Rowan & Allanheld.

Hartman, C. (2002). City for sale: The transformation of San Francisco. Berkeley: University of California Press.

King, J. (2005). Touch down in San Francisco today and, at first glance, the city casts the same spell as ever: (Taking shape: what's new in the City by the Bay). Planning, 71, 12-16.

Logan, J. R., & Molotch, H. (1987). Urban fortunes: The political economy of place. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Marshall, C. (2005, May 7, 2005). New stem cell research panel chooses San Francisco as home. New York Times, pp. A-11.

McGovern, S. J. (1998). The politics of downtown development: Dynamic political cultures in San Francisco and Washington, D.C. Lexington, KY: The University Press of Kentucky.

Mollenkopf, J. (1983). The contested city. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Molotch, H. (1976). The city as a growth machine. American Journal of Sociology, 82, 309-330.

Molotch, H. (1979). Capital and neighborhood in the United States: Some conceptual links. Urban Affairs Quarterly, 14, 289-312.

Shaw, R. (1998). Tenant power in San Francisco. In J. Brook, C. Carlsson, & N. J. Peters (Eds.), Reclaiming San Francisco: History, politics, culture (

Shaw, R. (1999). Reclaiming America: Nike, clean air, and the new national activism. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Shaw, R. (2005a). How elites are reshaping San Francisco politics; www.BeyondChron.org [Web site]. [Retrieved: May 16, 2005].

Shaw, R. (2005b). Will Stern's Example Wake Up San Francisco Progressives? www.BeyondChron.org [Web site]. [Retrieved: August 3, 2005].

Stone, C. (1989). Regime politics. Lawrence: University of Kansas Press.

Stone, C. (1993). Urban regimes and the capacity to govern: A political economy approach. Journal of Urban Affairs, 15, 1-28.

Walker, R. A. (1998). An appetite for the city. In J. Brook, C. Carlsson, & N. J. Peters (Eds.), Reclaiming San Francisco: History, politics, culture (

Whitt, J. A. (1982). Urban elites and mass transportation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Wirt, F. (1974). Power in the city; Decision making in San Francisco and Berkeley. Berkeley: University of California Press.

This document's URL: http://whorulesamerica.net/local/san_francisco.html

All content ©2026 G. William Domhoff, unless otherwise noted. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited. Please direct technical questions regarding this Web site to Adam Schneider.

mobile/printable version of this page

mobile/printable version of this page