| |

Who's Jewish These Days?The Meaning of the Surprising False Positives of George Santos and Anna Paulina Luna for Research-Oriented

|

|||||||||||||||

|

| Dianne Feinstein |

Deciding whether individuals are Jewish is a trickier proposition. Although for many people it is easy (both parents are Jewish, they are members of a Jewish congregation or club, or, most simply, they publicly identify as Jewish), for many it is more complicated. Sometimes one parent is Jewish but the other is not. For example, Dianne Feinstein, the soon-to-retire Senator from California, grew up as Dianne Goldman (yes, Goldman is on the list of 35 distinctive Jewish names). Her father was Jewish, but her mother was Catholic, and she went to Catholic schools. She married three men, all Jewish (husband #2 was named Feinstein). Can researchers conclude she is Jewish?

Not an easy question. We noted that there are four different ways to determine whether someone is Jewish. The first, based on Jewish law called the "halacha," asserts that someone is Jewish if they were born to a Jewish mother or have gone through procedures that allowed them to convert to Judaism. The second is simply based on conviction: a person is Jewish if they consider themselves to be Jewish. A third is based on a tabulation based on the religion of the person's parents and grandparents: a person is half-Jewish if one parent is Jewish, one fourth-Jewish if one grandparent is Jewish, and so on. A fourth definition is based on membership in Jewish institutions like synagogues or Jewish clubs. For the most part, for our research we have used the second criterion: if someone considers themselves to be Jewish, that makes social psychological sense to us. We are aware, however, as Laurence Tisch, one of the Jewish CEOs that we interviewed for our first book, reminded us, that sometimes what you think doesn't matter. As Tisch put it, "When Hitler came around, he didn't ask questions whether you were or you weren't — it wasn't what you said, it was what he said" (Zweigenhaft & Domhoff, 1982, p. 102).

|

| Walter Lippman |

The pressure to assimilate, especially the higher Jews rose in the class structure, is the primary reason for false negatives. Some, like Richard Darman, a senior government official during the Reagan and George H. W. Bush administrations, whose father had founded and been the president of a synagogue, and who had been bar-mitzvahed at age 13, married an Episcopalian and became one himself. Others who did not convert to one or another Christian faith no longer identified as Jewish. Walter Lippman, a famous journalist in the early twentieth century, was born to wealthy and assimilated Jewish parents. He never converted, he did not join any Jewish organizations, and, moreover, he refused to speak to Jewish organizations and even declined an award from the Jewish Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Now, however, we are confronted with two cases of what seem to be unprecedented false positives: two newly-elected Republican members of the House claimed during their campaigns to be partly Jewish, but these claims were subsequently, and easily, shown to be completely false.

|

| George Santos (R-NY) |

The first to come to light was that of George Santos, elected in 2022 to the House of Representatives from the 3rd district of New York (UPDATE: and expelled by the House 13 months later). In addition to false claims about academic degrees, athletic achievements, and entrepreneurial endeavors, he also told various audiences that his grandparents had fled the Holocaust and that he was Jewish. None of what he said was true. According to an article in Jewish Insider: "The 34-year-old congressman, who was raised Catholic, has alternately said he is 'Jewish,' 'Jew-ish,' 'half Jewish,' 'a proud American Jew,' a 'Latino Jew,' and a non-observant Jew, among other descriptors, even as genealogical records have shown he holds no familial connection to Judaism."

Santos was running as a Republican in a typically Democratic district — one of 18 districts nationally that went for Biden but elected Republicans to the House. It is the wealthiest district in New York and the fourth wealthiest district in the country; moreover, as of 2020, it had the third-highest percentage of Jewish voters in the country (almost 21%). He was eager to gain the support of Jewish voters, especially wealthy Jewish Republicans who are deeply committed to Israel. In one fund-raising talk, sponsored by the U.S.-Israel PAC, held not in New York but at Mo's Bagel and Deli in a Miami suburb, he won the crowd over by asserting that he was Jewish. Andy Fiske, co-chair of the U.S.-Israel reported that "He said, 'I'm halachically Jewish,'" and went on to note that Santos "made it seem like" his mother was Jewish (Kassel 2023).

|

| Anna Paulina Luna (R-FL) |

On the heels of the many stories about Santos' fabrications came another about Anna Paulina Luna, a newly elected Republican to the House from a district on the west coast of Florida that was redrawn between 2018 and 2020 so it included 35,000 more Republican voters than Democrats. Luna, whose mother is Mexican American but whose father was not, only recently began to emphasize, or even acknowledge, her Hispanic background. In 2015, when she registered to vote, she indicated she is "White, not of Hispanic origin;" four years later, in 2019, she updated her voter registration to indicate that she is Hispanic, and she changed her surname from Mayerhofer to her mother's maiden name, Luna. During her campaign, she also suggested in some of her public comments that she has a Jewish background — but not your typical Jewish background. She claimed that although she identifies as Christian, she was raised by her father as a messianic Jew (that is, a person who identifies as Jewish but who believed that Jesus is the Messiah). In addition, she claimed, "I am also a small fraction Ashkenazi." Interviews with members of her family indicated that her father was not a Messianic Jew, but a Catholic, and the immigration records of his father, who left Germany in 1954, indicate that he, too, was Roman Catholic. Moreover, as a young man in Germany, Luna's grandfather served in the armed forces for the Nazis in WWII (Alemany & Crites, 2023).

Desperately Seeking Diversity

What are we to make of these two false positives, and what should social scientists do in in this new era of truthiness and more blatant lies when it comes to trying to research the ethnic backgrounds of those who do and do not indicate that they are Jewish?

First, I still believe that the distinctive Jewish name technique provides a legitimate and fairly accurate way to estimate the percentage of Jews in large populations. It is only an estimate, and it might include some false positives and some false negatives, but it can be used both to estimate Jewish representation and track it over time, as we did for corporate directors between 1975 and 2011. As noted above, my use of the distinctive name technique to estimate the number of Jews in Congress and the number of Jews on the Republican Jewish Coalition were quite accurate.

Second, when it comes to individuals from families with one Jewish and one non-Jewish parent, like Dianne Feinstein, academics will still have to make judgments on a case by case basis, and this will depend on which of the many definitions of who is Jewish is applied. For some purposes, the one we generally used in the past will suffice because it fits well with the emphasis on the importance of a person's social identity in understanding their values and actions: if Dianne Feinstein says she is Jewish, even though her mother was Catholic and she went to Catholic schools, it makes social psychological sense to take it seriously. In other cases, where one's rejection of a Jewish background is revealing, as we think is true for Richard Darman and Walter Lippman (in those cases, what was revealed was how strong the pressures were to assimilate), we think these things are worth noting, for we believe that atypical cases can help us understand better what seems to be a general pattern — they can enrich and provide nuance to our interpretation of the empirical data.

Third, we need to acknowledge that the false positives of Santos and Luna indicate that a new dimension is on the scene when it comes to studying Jews in the power elite. It is, however, a new pattern but at the same time a familiar one. Domhoff and I have noted, time and again, that corporate leaders and politicians often provide misleading information (and in some cases lie) about their class backgrounds, claiming that they grew up with, or immigrated with, nothing, and then through their abilities and hard work made it big (one might call this the Horatio Alger syndrome; one classic book has referred to this pattern as "the log cabin myth; see Pessin, 1984). Roberto Goizueta, the CEO of Coca Cola from 1980 through 1997, was eager for people to know that he left Cuba for the USA with only $100 in his pocket, but he was less eager for them to know that both his parents were from families that were among the wealthiest and most powerful in Cuba, or that he attended a prep school in Connecticut before he went to Yale. Over the years we have given many such examples, and we also have shown how the obituaries of such corporate leaders often perpetuate their self-aggrandizing stories (Zweigenhaft, 2004).

|

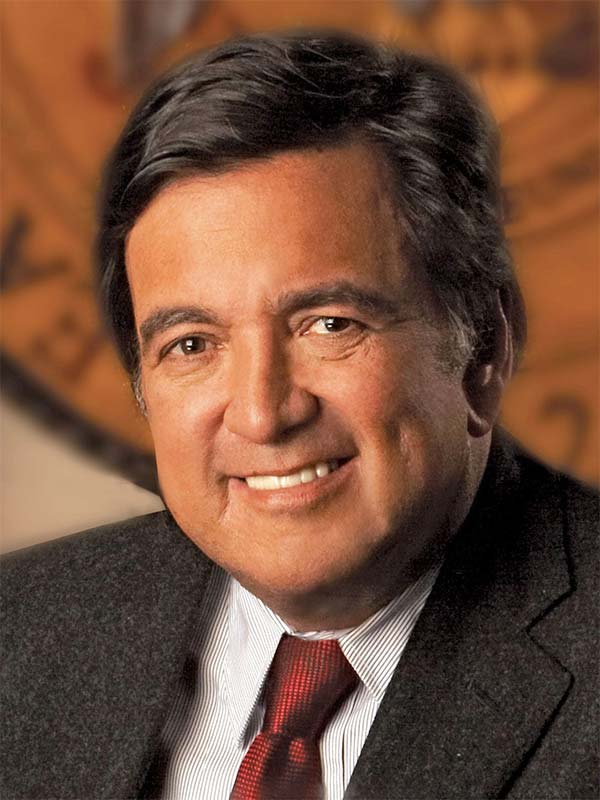

| Bill Richardson |

So, too, have we emphasized the need to ask questions about the ethnic claims that politicians and corporate leaders sometimes make, especially when they, like Luna, decide to emphasize their ethnicity fairly late in life because it has political or corporate benefits. When he ran for Congress, Bill Richardson began to see his Latino heritage as worthy of emphasis, but made no mention of the fact that his Anglo father was an executive at Citibank, that his Mexican American mother also came from a privileged background, or that he himself attended Middlesex, one of the most elite boarding schools in America, before going on to do undergraduate and graduate work at Tufts. (More typical is Richardson having exaggerated his athletic prowess, something we see with Santos, too, and something we have seen in many corporate and political leaders. Richardson did play baseball at his prep school and at Tufts, but he was not, as he claimed for many decades, drafted by the Kansas City Athletics in 1966; see Richardson, 2005).

|

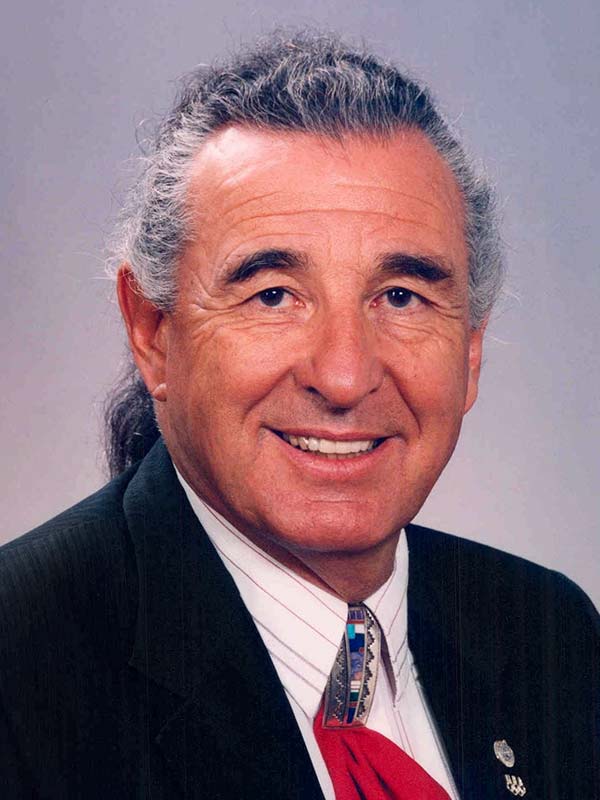

| Ben Nighthorse Campbell |

To give just one more example of a politician discovering his ethnicity at a time that enhanced his political ambitions, Ben Nighthorse Campbell, who was in the House from 1987 to 1993, and in the Senate from 1993 until 2005, is the son of a father who was part Apache, part Pueblo Indian, and part Cheyenne, and a mother who was a Portuguese immigrant. However, he did not join the Northern Cheyenne tribe and adopt the name Nighthorse as his middle name until he was forty-seven years old, a few years before he first ran for the House.

Richardson and Campbell, who chose to emphasize that they were in part Latino and Native American, were not false positives; they were simply late to accentuate actual components of their backgrounds. In contrast, Santos and Luna are indeed false positives when it comes to being Jewish; they claimed to be Jewish, or partly Jewish, but they were not. This suggests two things. First, it reminds us that in an era dominated by social media we are in an era of disinformation the likes of which we have never seen before. In the past, people in power lied, but now we have had a President who, according to the Washington Post fact-checker, lied or made misleading claims 30,573 times during his four years in office. As he seems to have as yet suffered no consequences for his lies, one can only conclude that for a public figure to be caught in a lie is not what it used to be. However, at the same time, we are in an era in which it is relatively easy to catch people in lies, because so much is easily accessible through the internet or through easily available records. The Washington Post could keep track of Trump's lies, and, to its credit, it did. Journalists who wished to check Santos' and Luna's claims were able to do so fairly easily and find them to be false.

Ambition to win office has always shaped how politicians present themselves. We have shown this to be the case in what they include in, or leave out of, their self-promotional books, in other written descriptions like those they provide to in Who's Who in America, and in what they say or don't say about themselves on the campaign trail. We have noted, for example, that although all five of the Republican and Democratic nominees for President between 2000 and 2008 went to elite prep schools, none was likely to mention it (George H. Bush went to Andover, Al Gore to St. Albans, John Kerry to St. Paul's, Obama to Punahou, and John McCain to the Episcopal School). Similarly, although Joe Biden can't say enough about things his working class father told him, or advice that he received from his high school football coach, his father actually at one point had a lot of money (he flew airplanes, he sailed yachts, and he played polo), and then lost much of his money due to bad business decisions compounded (or caused) by drinking. By the time Biden was in high school, a private Catholic high school in Delaware, his father was working as a used-car salesman, and indeed Biden's portrayal of the family as middle class at this point in his life is accurate, though incomplete (Entous, 2022).

What is striking about these two new Republican false positives, Santos and Luna, an openly gay male and a woman whose mother was Mexican American, is that they somehow thought that claiming to be Jewish, or "Jew-ish," or from a messianic Jewish background, would help them with the voters in their New York and Florida districts. Both the fact that they were chosen to represent the Republican party, and their bogus claims of some "Jew-ish" background, may speak to how desperately the mostly white male Republican party wants to be able to claim some semblance of diversity.

The lesson for social psychologists and other social scientists, then, is not a new one: we can't trust the claims people make, especially people seeking or in positions of power. Just as we have argued in the past that social scientists need to be skeptical about the claims corporate and political leaders make about their class backgrounds, or about their bona fides as Latinos, or Native Americans (or about their athletic prowess), so too do we now have to be cautious even when people claim to be Jewish, for they might only be making this claim because they think it could benefit them politically.

References

Alemany, J. & Crites, A. (2023, February 10). The Making of Anna Paulina Luna. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/

Entous, A. (2022, August 15). The Untold History of the Biden Family. New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/

Fermaglich, K. (2018). A Rosenberg by Any Other Name: A History of Jewish Name Changing in America. New York: NYU Press.

Himmelfarb, H. S., Loar, R. M. & Mott, S. H. (1983). Sampling by Ethnic Surnames: The Case of American Jews. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47, 247-260.

Kassel, Matthew (2023, February 14). George Santos Claimed to be "Halachically Jewish" During Election Campaign. Jewish Insider. https://jewishinsider.com/

Lavender, A. D. (1992). The Distinctive Hispanic Names (DHN) Technique: A Method for Selecting a Sample or Estimating Population Size. Names, 40(1), 1-16.

Pessin, E. (1984). The Log Cabin Myth: The Social Backgrounds of the Presidents. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Richardson Backs off Baseball Claim (2005, November 25). Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/

Rosenwaike, I. (1990). Surnames Among American Jews. Names, 38, 31-38

Shin, E.-H. & Yu, E.-Y. (1984). Use of Surnames in Ethnic Research: The Case of Kims in the Korean-American Population. Demography, 21(3), 347-359.

Waterman, S. & Kosmin, B. (1986). Mapping an unenumerated ethnic population: Jews in London. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 9(4), 484-501. https://doi.org/10.1080/

Zweigenhaft, R. L. (2004). Making Rags Out of Riches: Horatio Alger and the Tycoon's Obituary. Extra! The Magazine of FAIR, the Media Watch Group, 17(1), 27-28.

Zweigenhaft, R. L. & Domhoff, G. W. (1982). Jews in the Protestant Establishment, New York: Praeger.

Zweigenhaft, R. L. & Domhoff, G. W. (1998). Diversity in the Power Elite: Have Women and Minorities Reached the Top? New Haven: Yale University Press.

Zweigenhaft, R. L. & Domhoff, G. W. (2006). Diversity in the Power Elite: How it Happened Why it Matters (2nd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

Zweigenhaft, R. L. & Domhoff, G. W. (2018). Diversity in the Power Elite: Ironies and Unfulfilled Promises (3rd ed.). Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

This document's URL: http://whorulesamerica.net/diversity/whos_jewish_these_days.html

mobile/printable version of this page

mobile/printable version of this page