| |

|

|||||||||

|

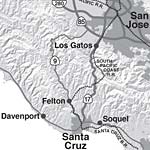

| Current highways and historical railroads in Santa Cruz and the San Francisco Bay Area [enlarge] |

While all this maneuvering and construction were going on south of Santa Cruz, Hihn caught a lucky break when two prominent San Francisco capitalists decided to build another railroad, the South Pacific Coast, through the mountains north of the city to compete with the Southern Pacific. Originating from the Oakland side of the San Francisco Bay, the 80-mile railroad required eight tunnels — two of them a mile long — that were built by 600 low-wage Chinese workers, 37 of whom lost their lives in the process.

Due to the new railroads and increased market access, Santa Cruz grew at a fast pace during the 1870s. It seemed likely that the good times would continue for decades when the South Pacific Coast opened in 1881, just in time to give the Southern Pacific a run for its money. The South Pacific Coast had a slightly faster and far more scenic route, but the competition was nonetheless very even, with both lines bringing about 2,000 passengers to Santa Cruz on July 4, 1884, for example.

But by the late 1890s, just when the growth coalition seemed to have engineered an ideal balance between industry and tourism (with a big assist from San Francisco capitalists), the city slowly began to lose its industrial base. The redwoods and other prime timber had been projected to last for 200 years, but they lasted less than 60, turning into housing, telephone poles, railroad ties, and fences much faster than anticipated. The increasing scarcity of tan-oaks, combined with a decline in cattle raising in the area, led to a shrinkage of the tanning industry to one company by 1900. As for the limestone industry, it reached its peak production in 1904 and gradually declined because the construction industry, spurred by the massive damage to buildings in San Francisco during the 1906 earthquake, began to use stronger and longer-lasting cement and concrete materials.

Technological advances in harnessing steam and electric power also meant industrial decline for Santa Cruz because saw mills and paper mills were no longer dependent upon river currents. Now they could move to larger cities, where demand was higher and there were larger labor pools. The blasting powder and gunpowder company, with the madrone and alder trees depleted (and by then owned by the DuPont Corporation), moved its operations to a plant north of Oakland in 1914. With the railroads fully constructed, and the Southern Pacific having no need for local equipment makers and repair shops, the foundries declined or disappeared as well. In 1881, Santa Cruz County was second only to San Francisco County in industrial production in California, but by 1900 it was already down to 14th in the list of 58 counties, and by 1910 it was 18th.

|

| 1935 postcard |

"Playground of the West"

So tourism became the main industry in Santa Cruz. Its main promoter was Fred Swanton, who was the third person, after Anthony and Hihn, who exemplified the general development of the Santa Cruz growth coalition. Born in Brooklyn in 1862, Swanton came to Santa Cruz as a young boy, where his father later built the first three-story hotel and included him as a business partner. He went on to make and lose fortunes in two ambitious ventures — the first hydroelectric plant in the West and the first commercial telephone system in the state of California. Starting in 1903 with the acquisition of bathhouses from an early pioneer of the Santa Cruz tourism industry, he soon created the Santa Cruz Beach, Cottage, and Tent City Corporation in order to add small overnight dwellings to his holdings.

Fred Swanton

You can read more about Swanton's various tourism efforts here; this site also includes many old photos of the Boardwalk area.

Fred Swanton with silent film star and Santa Cruz native

Shortly thereafter, Swanton expanded into a casino, rides, and a pinball arcade; after a number of setbacks, including a massive fire in 1906, his venture would eventually evolve into the Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk.

Taking advantage of connections with people he knew from his previous business ventures, Swanton was able to entice many notable people to vacation in Santa Cruz, including President Teddy Roosevelt, whose highly publicized visit in 1903 proved to be a boon to the tourist industry. To further help with his tub-thumping for Santa Cruz, the Southern Pacific Railroad provided Swanton with special booster trains that he personally rode to every city within several hundred miles, featuring brass bands and other forms of hoopla and honky-tonk. He loved to hobnob with the celebrities of the day and tried to make Santa Cruz an attractive place for the new movie industry.

|

| A 1947 "Suntan Special" arrives from the [enlarge] |

The Great Depression of the 1930s hurt Santa Cruz, as it did every other city, but not as badly as might have thanks to a new low-cost "Suntan Special" excursion train that the Southern Pacific instituted in 1927 as a way to make use of its commuter passenger cars on Sundays and holidays. Leaving in the early morning from San Francisco, with stops in Palo Alto and San Jose, the packed trains had a festive atmosphere as they snaked through the curves and tunnels of the Santa Cruz Mountains. They arrived at the beach and boardwalk just before noon to be greeted by a big brass band, and then left the city at 5 p.m., with many happy customers catching a nap on the way home. As many as 5,000 to 7,000 people enjoyed this sightseeing and sunbathing trip each Sunday during the depression years, arriving in up to seven different trains.

The Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk & Wharf

|

• The Santa Cruz Public Library's Local History web site includes a section on the history of tourism in Santa Cruz. There, you can learn about the "pre-history" of the Boardwalk, view dozens of historical photos, and read an excellent history of the boardwalk by Andy Schiffrin, one of the most important progressive activists from 1972 to the present.

• View an on-line album of historical photos of the Boardwalk throughout the 20th century. (Warning: the link plays calliope music!)

• Watch a five-minute video by KTVU-TV that recaps boardwalk history and gives you a feel of what it's like to ride the 1924-vintage Giant Dipper roller coaster.

• There are a few colorful books about the boardwalk available. Check out The Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk: A Century by the Sea, published by the Boardwalk's owners, or Santa Cruz Beach Boardwalk: The Early Years - Never a Dull Moment by Chandra & Richard Beal.

• A site about the history of railroads in the Bay Area features a page about the South Pacific Coast R.R. (1880-1940), including the "Suntan Special".

• The Santa Cruz Municipal Wharf, dating from 1914, extends from Cowell Beach and overlooks the Boardwalk. Learn more about its history from the City of Santa Cruz or the Santa Cruz Public Library.

UC Santa Cruz: a jump-start for growth?

The tourism boom didn't last forever. Santa Cruz was a lagging city in the late 1950s when the Board of Regents of the University of California announced in October of 1957 that it intended to expand the six-campus university system by adding three new campuses — one near San Diego, one near Los Angeles, and one 75-100 miles south of the San Francisco Bay Area in the area that is called the Central Coast. Well aware that there were several potential sites in Santa Cruz County, the local growth coalition pulled every string it could to win the bidding for the new campus. Its leaders decided that 600 acres from the old Henry Cowell limestone and ranch lands, in conjunction with 400 undeveloped acres just below the ranch, would be an attractive package, but despite enormous lobbying for Santa Cruz the Regents made a preliminary decision in December 1959 in favor of a site south of San Jose that had the advantage of proximity to the newly-emerging electronics industry in what soon came to be known as Silicon Valley.

|

| The former Cowell Ranch [enlarge] |

The Santa Cruz boosters persevered by drawing on their connections as graduates of the Berkeley campus to convince the Regents to reopen the question and entertain a revised proposal. Now all the land would be on the old Cowell Ranch, so the Regents would not have to deal with several different landowners. Furthermore, the price was lowered to a very attractive $1,000 per acre, about $250 per acre below the assessed value of the property, and the Cowell Foundation in effect promised to return $975,000 of the purchase price through a grant to build the first cluster of dorms, dining facilities, administrative offices, and faculty offices, which would be named Cowell College. The city and county offered $2 million in infrastructural improvements.

When the pluses of a Santa Cruz location and the strong pressures by the Santa Cruz representatives in the state legislature were stacked up against the problems that might develop if a San Jose location were chosen, the scales tipped in Santa Cruz's favor in December 1960. Within a week of the final decision, city and county officials met with representatives from the university to set a timetable for construction of the campus and access roads for an opening in September 1965. In what turned out, in hindsight, to be a fateful political decision that undermined the local power structure, the city council agreed to put those parts of the vast campus that were to be developed in the first 20 years inside the Santa Cruz city limits, to make it easier to provide water and other utilities.

With the campus planned for 27,500 students by 1990, the city leaders were overjoyed because they thought the city would grow from 25,000 in 1960 to 125,000 in 1990. Land values would increase immensely; plans were made to attract new industries and build office buildings.

Or at least, that was the plan. Learn more about what happened in the next document, "Progressive Politics in Santa Cruz".

This document's URL: http://whorulesamerica.net/santacruz/history.html

All content ©2026 G. William Domhoff, unless otherwise noted. Unauthorized reproduction prohibited. Please direct technical questions regarding this Web site to Adam Schneider.

mobile/printable version of this page

mobile/printable version of this page